JULY 2020

Click image for link.

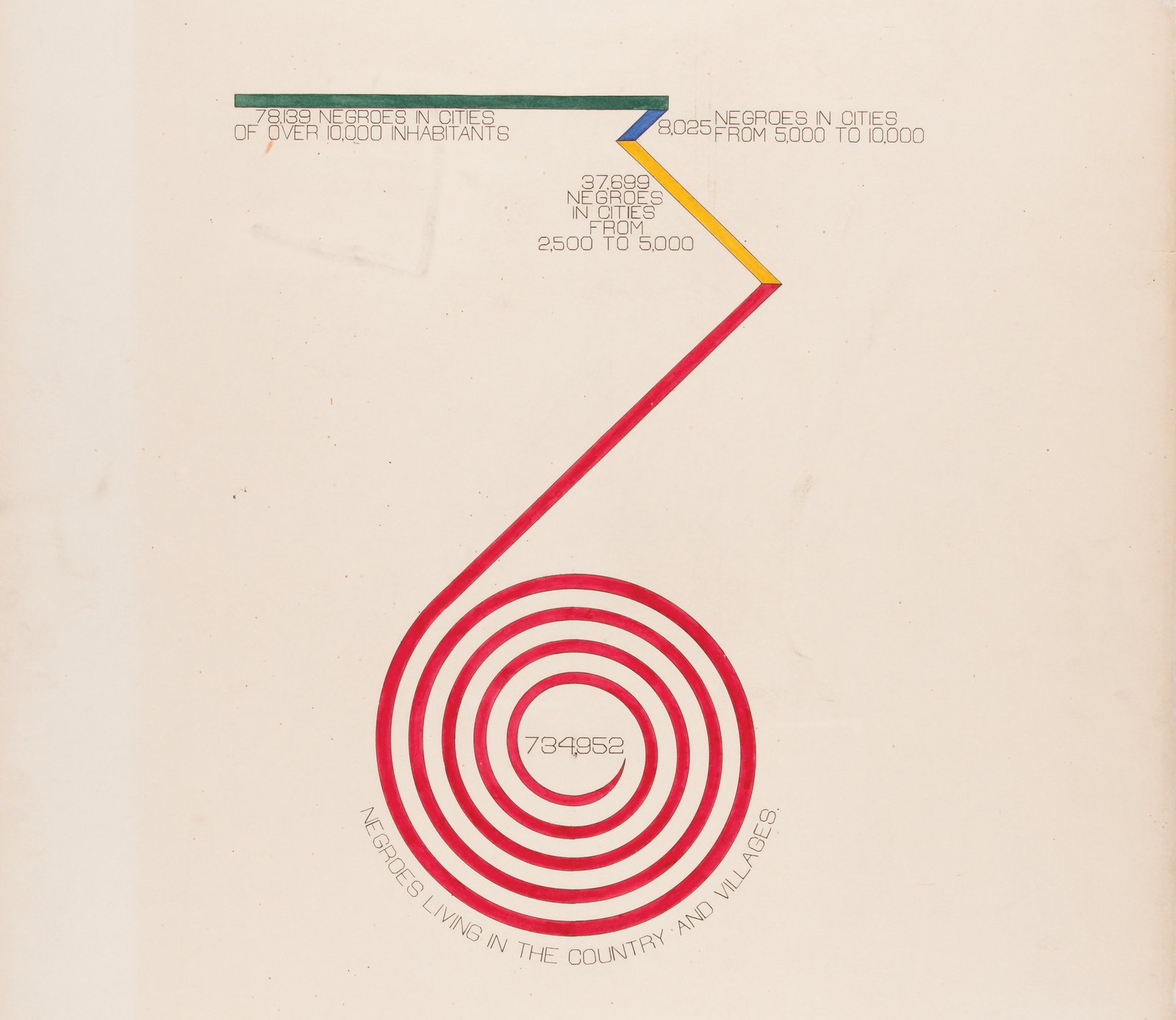

Credit: W.E.B. Du Bois’ City and Rural Population data visualization (1890). Photo: Library of Congress.

︎︎

Click image for link.

Credit: W.E.B. Du Bois’ City and Rural Population data visualization (1890). Photo: Library of Congress.

This essay situates political activist, sociologist, and artist (amongst many additional attributes) William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868 - 1963) within the foundational framework of Afrofuturism.

Read here.

Coined by writer and critic Mark Dery in 1993, the term Afrofuturism denotes creative works - artistic, literary and musical - that seek to envision a more equitable space for Black livelihood in the future. Implicit within Afrofuturism is a critique of a society where Black people currently are, and historically have been, victims of a multitude of systemic oppressions. Referring to Martine Sym’s theories of the mundane versus fantastic aspects of Afrofuturism in her film The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto (2015), in this essay I study specific actions and moments in Du Bois’ life in which he engages with both the “mundane” and the fantastical aspects of Afrofuturism. I position Du Bois’ political actions and sociologcal research, such as his debate with Booker T Washington’s 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” and his data visualizations in The Georgia Negro: A Social Study (1900), within the mundane aspect of Afrofuturism. Conversely, I frame Du Bois’ speculative fiction writings, such as The Princess Steel (1908-1910) and The Comet (1920), within the fantastical. By claiming Du Bois as a Proto Afrofuturist, I assert Du Bois’ contemporary relevance. Du Bois wrote from the same tech-driven core we use to operate big data with today. Perusing the clear afrofuturist mindset in the praxis of W.E.B. Du Bois’ life’s work helps to situate him firmly within the Black Radical Tradition.